Being a storyteller is somewhere in my framework. I’d like to think that’s the crux of this blog, to tell stories. This blog has lots of long-winded stories. It’s just one of those things that you’re gonna have to live with for giving an emotionally unstable person a keyboard and a WiFi connection. (That’s me) And whatever it is that I have to tell wouldn’t be complete without the mention of this place.

When I first started this blog, I made sure this was one of the first subjects I posted about, because it was, and still is such a big deal to me, following me around like a phantom through different stages of my life.

The chiseled granite block along the disintegrating roof line reads “Milton Co-operative Dairy Corporation”. Most folks in town call it “the creamery” unless you’re one of the few who are unaware of what the corroding property used to be. I’ve heard people speculate plenty of things, including a train station, a munitions factory or an armory.

The rambling building made of patchwork additions is off a side street in town, and the years run down its crumbling facade. Its forsakenness is obvious. Young trees have grown around and inside the building, disfiguring the structure. If you catch a glimpse through any of the broken windows or an open doorway, you witness a dark world made of peeling lead paint, reservoired floors and piles of fallen bricks, all cast in various shadows in the places the shine of the sun penetrates its way inside. In a state as non-industrial as Vermont, this location is truly a magnificent way to get your senses drunk. And it was this dangerous, virulent location that changed my life around age 12.

Around 1835, Milton’s agriculture scene shifted fads, from sheep based farming, to more profitable dairy. The town saw an increase in farming in the intervening years which began to put a strain on Milton’s original creamery, The Whiting Creamery, located off Main Street near where Oliver Seed is today. By 1919, many Milton farmers got together to form a dairy co-op. They built their headquarters on Railroad Street, a side street off Main Street, which today is one of the village’s primary thoroughfares. At the time, Main Street was actually the Main Street in town, and because titular Railroad Street paralleled the tracks, it was practical real estate.

The Whiting Creamery in Milton, circa 1905 | UVM Landscape Change Program

The building was done unconventionally, with a steel I-beam construction and stucco facade installed over bricks, which according to the late owner of the ruins, was a design unique for anywhere in Vermont at the time. Miltoner John McGrath would become the first president of the co-op. Over time, the creamery’s business ignited, as more farmers from Milton, and rural parts of northern Chittenden County and Southern Franklin County were sending their milk to be processed there – and shipped out. A lot of the revenue made by the creamery actually came from exotic foreign locations they shipped the milk to, like Boston and New York, via the aforementioned railroad that runs inches from behind the building.

In 1935, the creamery would expand for the first time at the height of the great depression in a conspicuous brick addition that today is the worst part of the complex. While most money-making things in the United States were prostrate in defeat, the railroads and the dairy industry seemed to be staying steady. Over the years, several more additions came along, and when cars became common, garages and a scale room were built, until the current uniquely shaped structure that exists today was finished. Those who can remember the creamery when it was functioning said that it was one of the largest creameries in western Vermont. During its most prosperous years, it would do over $5 million worth of business in a year, and employed 50 people. According to a homeless fella I accidentally met that briefly lived in a tent near the tracks behind the building, he recalled his father working there. “I remember how bad the milk lab used to smell” he said in fervent disgust at the memory. “Used to stink so bad, you could smell it down Railroad Street!”

During the cold war, the basement area was also designated as a fallout shelter, an appointed place to seek safety in case of nuclear destruction. Though, a practical observation at the grimy basement now days tells the visitor that the apocalyptic urgency so many people in the 50s were subscribing to would have easily vaporized anyone who decided to wait it out down there. Until recently, a badly warped caution-yellow sign that read “Fallout Shelter” in black lettering could be seen crookedly hanging from a concrete wall. Some local kid most likely stole it for a memento and hung it in their bedroom.

However, as time flowed, business practices changed, and the creamery soon found itself cutting its teeth on the stone of the changing times. McGrath would resign as president in 1953, and Ray Rowley, from another long-standing dairy family in town, would take control. But the Co-Op was already shaking hands with its mortality.

By the 1960s, the creamery’s fate seemed poised to continue percolating in some downward lament. A decline in dairy farming led to a decline in dairy – the stuff that created the business in the first place. It was around this time when bigger monopolies began to appear on the scene, a trend which has only intensified since then. Larger and more resourced operations like HP Hood in Burlington were hard to compete with, and the growing struggle of irrelevancy disarmed many smaller businesses. Sort of ironic is that HP Hood is also long gone, the old plant on the corner of King and South Winooski has been modernly renovated into condos and mixed commercial space, as is the cool trend with defunct industrial properties.

The last 2 decades of the creamery’s life were slow death. Fluctuating milk prices and the cost of refining didn’t show up in the farmers’ paychecks, which irritated some of them. I can’t say I blame them, farming is hard work. A crude barn shaped structure was built next door, and was ran as “The Milton General Store” for a while – an appendage of the creamery. Those who still remember it, say that it was the kind of place where you could literally buy anything – from nails to maple syrup, and had a distinct “dusty workshop smell” inside. But that attempt at savior failed as well, and by 1974, the creamery became a ghost.

The building was put up for sale, and shortly afterward, was purchased by a local gentleman who used it as storage space for his many antiques and the miscellany he either collected or hoarded. That line was a blurry one. But it was clear that this guy was of his own sort. Sadly, mental instability and his own demons got the best of him, and one of the consequences was that he neglected the place. His paraphernalia became either stolen by characters who have no moral issues with thievery, or what was left behind rotted away when the building began to progressively weaken, and rats began to nest inside.

I had struck up a few conversations with the owner before in my teenage years. I used to work at a local gas station then, which was a crash course on social skills for this young Aspergian and his seemingly incompetent switchboards, but the struggles also brought some worthy experiences. Like getting to know him a little better whenever he’d stop in. I knew who he was, but our getting acquainted was a bit coincidental. He’d see me working and just start chatting with me if he was in my proximity, but he seemed a bit lonely and he’d chat with anyone willing to lend an ear. Over time, he began to recognize me as a regular working stiff and always made a point to have some sort of small talk with me, on his own terms anyways. I found out that he was a pundit on Milton history, or really the old in general. I’d risk getting reprimanded by my shift manager and have conversations with him about local history and things I found to be fascinating – information that I didn’t have access to anywhere else. But due to his schizophrenic-esque behaviors, I had to try to be mindful of how I engaged with him.

I found out about his death in the summer of 2016, which saddened me a little. I’m sure he had so many stories and secrets that he took to his grave with him that we’ll just never know. I always contemplated taking the time to contact him and ask for an interview, but anxiety got the best of me. The creamery was hastily and quietly sold, and condos were spoken of. I suppose the momentum didn’t surprise me. Milton-ites have wanted to get rid of the scorned property for decades. Which is also why I’m re-submitting this blog post. The creamery wasn’t just the first place I had ever explored, it was a huge part of my adolescence. I’ve never dealt with change that well, so when I got word of a change coming up in the form of the creamery’s possible demolition, I decided I needed a fond farewell.

I’m going to borrow a quote from the late Leonard Cohen, when he said; “I’m interested in things that contribute to my survival”. The creamery (and Mr. Cohen) has contributed greatly and artfully to my survival and I’m forever grateful. It’s weird to think about as I’m reminiscing and drinking a beer right now – how different would my life have been if I didn’t grow up in walking distance of this place? Did any of you folks have an abandoned building in your hometown, or a place that was a local rite of passage to visit as a kid? Do you have any stories of your first adventure?

Over the years, I struck up a friendship with the great folks at the Milton Historical Society, and one of my first research topics was the creamery. Sadly, not a great deal of information about it really carried over the turn of the most recent century. For the most part, I compiled all the usable information I could in the paragraphs above this one. But that’s not all. Museum curator Lorinda Henry was kind enough to scan for me some historical photographs of the business in operation, and portraits of its employees.

Folklore

I think one of the most memorable things about the creamery, and my childhood affixion to it, were the ghastly urban legends and ghost stories that the older kids told me, a ritual I continued when I aged. Stories that created an inseparable impression about the place.

Murder

I still remember the first story I was told, which I think is also the most popular one in some variation or another. The story of the murdered janitor. Essentially, two custodians were working graveyard shift, and a known rivalry was between them. That particular night, one of them would let all of his animosity towards the other cut loose like a pressure valve. Somehow, one of them fell off of a two story catwalk which is suspended above the scale room, broke his neck when he hit the concrete, and died in the building. The motive, whether it was preempted murder or a moment of unchecked anger isn’t translated into this tale. But the aftermath is. The other employee realized the gravity of what just happened, and he was frightened. He’d be blamed. He’d go to prison! No, he couldn’t let that happen. So, he decided to make his co-worker’s death look like a suicide.

Transporting the body upstairs, he hung him from a meat hook in one of the coolers, hoping when the corpse was discovered the next day, that’s exactly what the shocked observers would believe. Only, they didn’t, and apparently, according to an increasingly vague story line, the assaulting janitor was accused of the crime. The story splits into a few endings from here. One says he was arrested, acquitted and sentenced to prison. Another version tells that he skipped town, and successfully vanished from those who wished to prosecute him. As the older kids told me, the residue of the departed janitor still skulks around the building, which seems to be his tomb in the afterlife. Though not much is known about his apparent haunting, people have admitted to feeling uncomfortable inside, like they were being watched by some unknown specter, especially by the room where his body was hung. Phantom chills and disembodied noises have also been reported, but whoever was the one coming forth with these claims remain a mystery. The historical society couldn’t give me any hard evidence of a murder at the creamery, or even a death, so this spook tale remains in the realm of urban legend.

Broiled Alive

I remember another, far more ghastly story. I was shown a large rusted vat inside one of the many dark rooms of the basement, leprous with peeling paint, dankness and dripping water trickling down overhead. A dim mag light beam illuminated the robust fixture, and it was filled with some sort of unidentifiable glish. As the story goes, sometime in the 30s or 40s, a young man was tasked with making powdered milk, and somehow, fell into a vat of product heated to boiling temperatures. His skin was filleted from his body and was unable to be saved. A more macabre version of the story was that crooked business practices just distributed the milk afterward because losing money was a more grim thought than their customers drinking liquefied employee.

Well, I couldn’t find any validation on that story either – but the historical society did help me dig up a very brief newspaper snippet from the 1940s, about a boy who did die in the creamery in those days before child work regulations, but the cause of his death wasn’t specified. But one look at the gross vat today does make a good totem for a story like this one, and the basement is a creepy place. Not surprisingly, there have been quite a few reports of feelings of unease down there.

The Homeless Man

Another notable story did happen, and is documented. Sort of. In the 1980s, recently after the building had been abandoned, a homeless man got inside and planned on spending the night. But nothing stays warm in the wintery cold, and he decided to get a fire started. The details here vary on what happened, but somehow, him and the old couch he was sleeping on, became engulfed in flame. The man died on site. Speculations vary on how he died, whether some flying cinders landed on his sleeping form and ignited his clothes, he was drunk and knocked over or fell into the barrel he used to put the fire in, or some hoodlum kids decided to harass the guy, and wound up setting him on fire. Either way, a dead vagabond was the result. Today, there is a pancaked and charred couch on the ground floor, which I was told was the very same one he died on. Though that too is unverifiable. Some ghost enthusiasts like to think that the homeless man adds to the creamery’s fabled layers of ghosts.

That may account for a claim I heard around 2009, when someone told me of a strange experience of theirs. As he was walking by the creamery at night, he saw a ‘black cloaked figure – almost like a robed monk’, moving in the same direction as him as he walked by the building down the railroad tracks on his way home. He could easily distinguish the thing thanks to the dirty yellow glow of the street lights coming through the second-floor windows, giving the figure a distinct outline from the shadows. His claim wouldn’t have been as weird if it weren’t for the fact that he saw it walking in a part of the second story that didn’t have a floor.

The Tunnel

My favorite hearsay was of the old tunnel. In my teenage years, when I began to become more intimate with the building, I was acquainted with a piece of Milton lore; about a tunnel, which supposedly led from the creamery, all the way down Main Street underneath several of the old houses before dumping out near the Lamoille River. My teenage mind sort of just took that in as fact, and I began making trips down to the basement trying to find the opening, or a trace of a sealed up door. I did find something, a door below ground level, that had been cinderblocked off. Most likely, that was the old tunnel, and years later, parts of the blockade were sledgehammered through, giving me a glimpse. The tunnel was there all right, but didn’t run all that far. I could see the collapsed section yards from my position. It actually ran to the brick building next door. Today, its apartments, but it was originally built as another part of the creamery, which is why the tunnel was there, and which is why it was sealed off. I spoke to a few Milton old timers, who smirked and recalled breaking into the tunnel when they were younger, and sneaking beer and cigarettes down there. But was there ever a passageway that ran all the way under Main Street? Well, I wrote about that, if you’re curious.

As for me? Well, I’ll admit that my experiences being a tourist to this old building haven’t been all that paranormal. I generally don’t concern myself with hauntings or ghosts anyways, unless one of them walks right up to me and says hi. It’s not that I don’t believe in those things (I write about weird stuff after all!), I just try to take an agnostic approach first. I do have one strange personal account though. In 2011, I was walking up to take some photos, and found a very strangely placed mannequin inside one of the old coolers upstairs, propped right in the doorway so whoever walks by would notice it. This one was particularly creepy. It looked old and decayed and yellowed, and dressed in a patchwork of old clothes. There was also a pentagram carved into its neck. I went to other parts of the building and doubled back about 40 minutes later, and the thing was gone. I never heard or saw anyone come for it. To this day, I still don’t have much of an explanation for that weird event.

I still recall one person writing to me when my old post was live, and told me how they found old co-op milk jugs that had been found underneath their old concrete front steps. They had apparently been used to help build the framework for them, which wasn’t an unusual practice for old Vermonters, who used their ingenuity to use whatever materials they could for their benefits. Milton’s Main and Railroad Streets are old. It makes me wonder what else is found within these old homes.

Painkillers and a Purpose.

This is the section where I get emotional and hash out my scars. If you don’t dig personal backstories or revelations, skip down to the pictures. There’s lots.

Growing up in Milton, I was a shy, creatively maladjusted boy. As the years and my youth passed on, not much changed, apart from my curiosity, and me never feeling like I was comfortable in my own skin. I was always thinking there was something wrong with me. Being diagnosed with Aspergers at a young age, I quickly found out that I was a pundit on certain things, but hopelessly inept with others, like social skills. It was an unhappy balance, and that led to a coming of age where I was bullied and timid.

I suppose it’s fitting that I began to take interest in what we perceive as oddities, or things that don’t fit our conception of the illusion of normal – and their captivating stories. Abandoned places fell into that category for me. The creamery was the first. And better yet, it was easily accessible.

I first dared to cross that threshold into a world that conventional wisdom told me was dangerous and forbidden. And that’s partially why I wanted to venture inside, and why I decided to repeat that ritual for years to come, because people frowned on those sort of behaviors, and I wanted answers for myself.

The thing is, I’ve never been like everyone else or satisfied with the pre-prescribed banalities of everyday life, things that are all too generic and sanitized. Whether it had to do with growing up Aspergian, or be it something in my framework, I never fit in. So I decided to put myself in haunted waters, and see what happened. Turns out, bending the rules, thinking for myself and daring to go against what I was taught was one of the best things I ever turned into a habit – and is some of the best advice I can give to anyone, assuming I’m asked for my opinion on these things.

Everything is a language, everything is constantly trying to tell us something or express itself in its own way. The trick was learning how to discern the signals from the din of chaos. It was the first abandoned building I ever explored that fired the engines of desire and curiosity in my mind. It was in those precious hours inside where I heard an obsession being born amidst the damp cold and watchful eye of wild shadows that would haunt me for years to come. Treading over the debris littered floors, slowly opening crumbling doors, peering into a vast basement filled with water and intimidation, the dark becomes your hunting grounds, in the foreground of endlessly dripping water.

I spent most of my 20s in dislocation and learning about the blues while slowly murdered by my anxiety. I was depressed, lonely, still trying to figure out my autism diagnosis, and going through the trials and tribulations of several different antidepressants or booze. Sometime in between all of that, I lost myself trying to please everyone. In those years of learning what heartache brings, I waltzed between things that I did that brought regret and just trying to get by. By age 25, I had given up on myself. I spent years running from nothing but those vicious, self-depreciating thoughts in my mind and not only did I feel inferior to everyone in the world, but I lost faith in people, and hoping that anyone would understand. I even attempted suicide. They say that you grow up believing the narrative we’re told by society, and how people treat you. Either you had it or you didn’t, I guess. I couldn’t be the only one who felt there had to be something better than the imposed adult lifestyle that was bounded by convention. I knew I wanted more.

My tendencies to escape from the pressures of a judgemental society raging over me and all my failures brought me to these forsaken locations. When things got too rough outside, my earnest self climbed inside. My time hanging out in them not only became like therapy for me, but it also picked me up like a drug as unacquainted fires lit sparks in me that took me years just to understand their ways. Urban exploration helped me confront social and emotional turmoil, as I’d disappear into a sea of rebirth, or at least a change of scenery.

It was here where I could try on my heart, and let my walls down. Over time, I didn’t really mind that I was lonely because it felt like home. Whatever things ran through my mind I could keep for myself. I could learn about myself and my environment and observe both and how they changed with the weather. I could study these ruins and what was left behind, getting an extraordinary and authentic look at a sort of museum of humankind than I could ever learn elsewhere as I picked at the bones. Building materials, architecture, electrical and plumbing, amateur archeology, hazardous side effects, irrelevant culture – all things that would give me a better understanding of the world around me, and conjure more questions and a desire to learn. I could learn to gauge my anxiety and problem solve in different ways.

Little did I know that while I spent so much time in the edges between self-awareness and self-loathing, I grew as a person.

Photography was something I picked up in relation to urban exploration, as I pushed myself to learn the mechanics and how to capture this world that I saw. I really digged the feelings I was receiving, that excitement, that push to keep trying, to keep dreaming. I wanted to get lost because I couldn’t be found. When we’re presented with things that we don’t see in our routine days, we get curious and we look. Social norms often tend to discourage looking closer in real life, and that’s why I love photography. It allows us to do so freely.

I still remember the satisfied grin on my face when I first bought my own camera with money that I had worked so long to save. And the creamery was where I honed those skills. Exploring enhanced and enlightened by appreciation for the landscape around me, and matured a sense of wonder in these everyday spaces. Being a photographer really enhanced my self-esteem and gave me a distraction from everything that was bringing me down. Every photo tells a story. Every photo was taken by someone who had to be at that place, who did the planning, who had an experience to share.

In college, I majored in graphic design, which, despite me falling out of love with it after I became wise to how the industry works and how that didn’t fit me, has greatly influenced and improved my imagery and my hobby. I could further my creativity with all that was still stuck in my head.

Writing has something that always came sort of naturally to me I guess, but it’s still something I’m pretty self-conscious about and always trying to develop. Twisting the night away in front of the comforting glow of a computer screen as I listened to those records that almost hit harder than my pain, I tried to translate and find a meaning in my thoughts and experiences and explores. Especially as I grew older, I wanted to spin a thread from my past into my present and try to find a meaning to my suffering, to these forsaken locations, and how being a human is one complicated gig.

I definitely wore my heart on my sleeve, and I remember all the things I felt discovering my favorite albums, the heroes I would worship, fascinating local weirdness and just about anything else that made me shiver. Part of me wanted to contribute, to create, to make sense of everything I could. What do I do with all these feelings and experiences, these things that are crawling up inside my head in my 20 something-year-old wasteland?

I’m not sure what it is about the creamery, or these temples that are a relief to me, but they make great atmospheres to drain my mind, all the more so when my cup is full.

Exploring ironically became some sort of a social endeavor for me in my young adult years when I was searching for friendships and other libertines. I’d often accidentally meet these amiable, intelligent people with the same interests, and I’d take the chance and meet them in person and go on adventures, and I’ve been lucky to form a few strong bonds because of it.

Before I had this blog, I had a Flickr account. In those days, Flickr was really a niche audience. But somehow, my Vermont-based photographs made their rounds, and over time, others started to reach out to me. We would bond over the places we’d shoot and our stories, and sometimes, if we really hit it off, we’d meet up in person and find new exploratory joys (but to be honest, the biggest thrill for me was to finding new places myself). I think any other explorers can vouch for this – that the conversations you have while adventuring are often the best, and the weirdest. I’ve had plenty of amusing chats underneath the creamery’s arched tin ceilings. That’s how I met my friends and role models Rusty and Christina who run Antiquity Echoes and Dan from Environmental Imagery, to name a few.

The internet introduced me to the “urban exploration” community, which was still emerging at the time and pretty underground, and I remember being curiously thrilled that there were other people out there who did what I did. The explorers (“urbexers”) who were creating websites and putting their photography online, I found, had scars, philosophies, and interests similar to mine. And their work was good, it was venerable, and it gave me a direction. I love people who add personality to their work.

That was also where I was introduced to the term “urbex”, something that attempted to categorize what I was doing. Way different than the modern day urbex explosion that has crawled all over the internet, and alongside the greats, an oversaturation of various disrespectful types who are more into their own vanity and bravado and taking pictures of them smoking vapor cigarettes than the tourism, which often brought drama and something pathetically similar to high school cliques in the social media groups I used to be apart of (another attempt at trying to fit in), so these things turned back into a private affair for me.

I don’t want to be a trite person because that’s unfulfilling and there is no point in following this blog if I sound like everyone else. I’m me, and my thing is to be upfront and honest about where I come from, and often, I talk too much. That may not be everyone’s scene, but I’m okay with it – it’s all I got. It took me years to find my words and a beat, and I’ve learned a murderers row of personal lessons from it.

I’ve been searching all my life for a purpose, some sort of connection to this “humanhood” we’re all supposedly a part of – but I never really found it until I started learning how to live in the present tense and brave through the pain and uncertainties. You have to be vulnerable to grow, and sometimes, letting down my guard was a significant and valuable thing. Proving the static in my head wrong, that I wasn’t too far gone to have a talent.

Exploring, photography, writing, they all sort of united together, and as I chased them, I fell for them. I wasn’t wasting away my soul anymore, and I learned to stand on my own and begin again as my purpose worked its way to the surface. I wanted my life to matter, and for my time to have a positive impact and not to simply pass me by, even if it costs me. I don’t want to just survive, I want to do the best that I can to create a wonderful life. Especially now as my youth and years are passing me by.

Nothing will ever be handed to you. You gotta work hard, or it will never happen. If you want to be an artist or wield a talent, you have to study that art. Get the books, the role models, the media that has to do with what sort of person or thing that you feel you want to become. Study it all the time. Practice, learn, stumble, keep practicing, go. Decide, who are you trying to be? And what’s the motive? Do you want to be an artist that cares about your art, or famous? Those are 2 completely different things. I’d rather be trying to be the best I can be at whatever I’m doing, even if I only have a few other people that happen to like it.

For someone who didn’t believe he had much of a future after he had left college and feels like he’s spent his whole life less up than his downs, this has turned my whole life around. It’s the long haul, but it’s worth it. I try not to put anything out there that I don’t believe is good. Even if that means a lot of time in between my newer posts. Quality is more important to me than success. And I’m still finding my beat and my voice (and still cringing at my earlier posts haha).

I learned that I can succeed even when I’m failing miserably. I learned not to be as negative as I used to be, and indulgence can be a good thing in moderation. Enjoying a little danger now and then is fun and beneficial, and remembering where I came from doesn’t have to be a condemnation. Being willfully ignorant will get me nowhere, and is counter-productive to the life I want to live, or the people that help me shine.

Others are imbued by my weather, and I flourish in the presence of love. Fear gets me nowhere. Anger and indignation can be useful and rejection can make you resilient. In pain there is wisdom. Waiting out my life to hold onto anything never worked.

I re-wrote this blog entry and re-photographed this place for myself, the people I know now, and those who became ghosts, because I think there is a great story being told here. Our beginnings and ends are all written in the choices we make, and they all lead us in a direction.

In this struggle, something can be found, and it shouldn’t be measured by what conventional wisdom has imposed or implied. It’s the experience that means everything. In some ways, I’d like to hope my story can be several of us. And after all I’ve said here, I’m still shaking as I consider hitting the publish button. If you don’t say anything, you’re not vulnerable.

It took me 28 years to stop playing my old records, to get beyond that point where I couldn’t seem to move on yet knew I couldn’t stay the same. Now, I’m writing this up in an apartment 24 miles away from where I grew up, and where I spent my youth in imagination or hopelessly devoted to misery. Life moves on and our stories are always more connected than distance implies.

Requiem Revisited

The town I grew up in left a long time ago, and we lost touch as I shed my skin. Now, with the creamery’s uncertain future and Hyde Manor’s weight taking over and speeding its collapse, I felt like two of the most influential figures of my past lives, things that really shaped the person that’s writing this right now, are vanishing. And they’re dying breeds – venerable buildings built with a motivation and with dignity, things that our new disposable and tawdry society shamefully doesn’t value. That’s more or less evident with all the pop-up cardboard condos appearing in town. It’s a shame that future generations of curious kids or explorers will loose these mysteries and interactions that are kept inside these constructions that they don’t build anymore.

Because I taught myself the basics of photography here, I thought it was ironic that all the photos I had of this place didn’t really reflect how much I feel I’ve progressed over the intervening years – and I definitely felt like out of all the locations I’ve documented, this deserved good representation. So I was on a bittersweet mission of reverence; to record every corner of the building and do a good job at doing so.

My friend Josh and I got together and decided to spend as many days as we could stomping around the creamery with camera equipment, our footsteps the only things haunting its rooms.

I wonder if I would have even gotten into exploring to the extent that I am now, if it wasn’t for my time spent here and the spell I was under. Would I have ever gone to Hyde Manor? Would this blog be existing? I can’t say if this place that has driven me crazy will fall and fade or not, but I’m glad we let our distress push us back to this old haunt and all my forgotten ghosts. But if I never see it again, well, I’m damn appreciative of my time here.

Thank you for the indulgence here. Part of me was almost against posting this last section, but my feelings that it was somehow meaningful and cathartic overpowered the fears of showing my scars.

I think the Lawrence Arms said it best; the time is never right, the words are never right. I hope it’s helpful. I hope it fires you up.

Historical Images

The newly constructed Milton Creamery. The ground still muddied and rutted from building it. 1919. Via UVM Landscape Change Program

Circa 1930. Via UVM Landscape Change Program

Collection trucks in front of the creamery – Circa 1930. Via UVM Landscape Change Program

The original Creamery, before the brick edition and the front garages. Courtesy of Milton Historical Society

Railroad view, Notice the massive water tower and the absence of the brick edition. Courtesy of Milton Historical Society

The Creamery Today

According to local lore, this is all that remains of the couch that the homeless man burned alive on years ago.

According to local lore, this is all that remains of the couch that the homeless man burned alive on years ago.

We found several animal bone fragments in the basement. According to my friend, years ago, people used to have illegal cock fights down here. Over the years, the decayed corpses of dead cats and skunks would also appear. Once, some folks, probably teenagers, stole road flares and had what we guess was a road flare fight down there as well.

A reality of abandoned places. They’re very commonly breeding grounds for stuff that hates us. Stuff like mold in a Pantone book of colors.

Always a good reminder to look down, you might be surprised at what your feet crunch over. Like shards of old china plates.

The sections of the basement area that ran alongside the railroad tracks were chopped up into several smaller rooms and passageways. In one of them, we found a crooked, rusted ladder that scaled up alongside what appeared to be a giant vat. So, up we climbed to check it out.

Here’s a shot of the former tunnel entrance, from the basement. If you notice the indented cinder blocks with holes sledged into them back against the wall – below where the light is working its way through the boards, that’s it. The eerie and dank basement levels here were dug down two and a half stories deep, with slate ceilings to insulate and keep in the chill. The foresight in its design worked. Even in the most sultry summer months as a kid, I remember it always being chilly down here in the dark. For half the year, the subterranean areas are a reservoir of stagnant water and the waste of the decaying building.

A little DIY reading was found in the dark and the damp of the basement area. It was a moldering manual on how to properly run a creamery. It’s fragile pages pretty much covered how to properly clean and sterilize both the machines and the milk, and how to pasteurize it so people won’t get sick.

Howe scales came from Rutland, and besides Saint Johnsbury’s Fairbanks factory, was one of the domineering weighing apparatuses found around Vermont. The Howe factory went defunct years ago, and it’s great building was converted into mix commercial and office space.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly!

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4

The hill country up near hardscrabble East Richford is an older, left behind Vermont of farmhouses with sagging rooflines, boarded up country stores, rivers, rusted iron railroad bridges over narrow underpasses, and toothpick rows of harvested corn stocks left in bleak fields.

It was up in this part of the state under 6 inches of snow and roads that made me thankful for snow tires that I was going oddity hunting.

We were the only car on state route 105A, a pretty desolate spur road connecting route 105 to a sparsely used border crossing at Sutton, Quebec. The bad tarmac ran alongside the hypothermic waters of the Mississqoui as the snow began to tumble down to the ground in an amiable silence. “Man, I love roads that follow rivers” my friend enthused. “Yeah, roads that follow rivers are some of humankind’s’ best achievements” I returned, and we both cracked a grin.

We continued to be the only traffic as we turned onto the dirt main drag of East Richford, which was only a few older wooden homes in various states of decrepitude. Past the abandoned Gulf station, the road sharply right angles at Quebec before beginning its ascent up into the border hills. We passed an old graveyard where the invisible line between the two nations slashed through the middle of, before my friend suddenly stomped on his breaks, our car skidding for a few seconds on the slush and ice. “Oh……” he breathed, looking at the granite boundary marker to our right. “Shit, are we breaking the law? We’re in Canada! Don’t we have to check in?”

“The only law we’re breaking is the law of gravity!” I quipped.

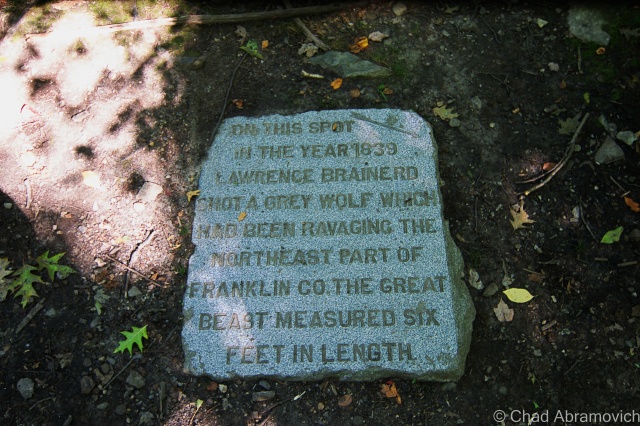

According to Sir Isaac Newton, objects fall. No exceptions. But if Franklin County lore has a flicker of truth to it, perhaps not.

This remote border road that made it’s way through some of Vermont’s most stark and impoverished back country near East Richford is known as “Richford’s Mystery Spot,” according to Joseph E. Citro and Diane E. Foulds in their 2004 book Curious New England: The Unconventional Traveler’s Guide to Eccentric Destinations. The “mystery” is that gravity in this spot reputedly likes to behave unorthodoxly. For example, cars are said to roll uphill! WTF?

These oddities aren’t unique to the Green Mountain State. Various places around the U.S. manifest the same puzzling phenomenon. Nearest to Vermont, there are two “mystery spots” in the Massachusetts towns of Greenfield and Harvard, and one in Middlesex, N.Y., on the awesomely named Spook Hill Road.

Citro and Foulds reported that they weren’t able to locate Richford’s mystery spot. Years ago, in a brown and bleak November, I made my own attempt. Being an avid Vermont enthusiast and local weird worker, I couldn’t pass this one up. I enlisted a friend, who couldn’t contain his mirth when I explained we were aiming to defy gravity, and quickly signed on for the road trip. I guess breaking the laws of physics is a good way to make plans.

The mystery spot is aptly named, I discovered when we turned east out of Richford village toward the looming form of Jay Peak, because it’s no easy place to find. The night before, I had consulted the state atlas and decided that the most likely location was the curiously named East Richford Slide Road, a hilly dirt byway that rolls over the foothills of Jay Peak with a few trailers and abandoned farmhouses along its length, before depositing you back on Route 105 in Jay town. It serpentines over the border a few times, but because you can’t get anywhere in Canada unless you hike through miles of mountain wilderness, the crossings aren’t guarded.

So how do you discover such an area? There had to be a first person to be bewildered here. My research had identified the late Dolph Dewing of Franklin as the first person to report experiencing the mystery spot’s effects in 1978. According to Citro in Weird New England: Your Travel Guide to New England’s Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets, Dewing started by sharing the discovery with his friends, then brought a busload from the Franklin Senior Center to witness the phenomenon.

In October 1985, County Courier reporter Nat Worman accompanied Dewing to the spot and watched as he stopped his 1979 Dodge there and revved it to prove it was in neutral. After about 60 seconds passed, the car began rolling uphill, accelerating gradually from 10 to 15 mph.

My friend and I weren’t so lucky on that windy November day. We parked our car in several places along the rural road and waited. Despite our relocations, nothing happened.

We pulled over again and mulled things over. Did we have to be in Canada for the “mystery” to work, or on the Vermont side? Maybe we just hadn’t found the right spot.

Sitting beneath border skies as the sun shone off the hood of my friend’s Chevy, I wondered if Dewing had been fooled by some sort of optical illusion. Was it really antigravity? Or magnetism? Or a hoax?

Researching later on, I found that the answers may be closer than I expected and rooted in the rational. There are a bunch of “mystery spots” around the globe, some with equally evocative names such as “gravity hills” and “gravity roads.” So, do the laws of physics simply stop applying there?

Nope. What baffles tons of spectators is actually an optical illusion, one that’s been debunked by physicists. Or, at least, that’s the prevailing theory.

“Gravity hills” and the like are places where the geography of the surrounding land produces an illusion, making a downhill slope appear to go uphill. Obstructions on the horizon can be a key factor in creating this illusion, because they rob us of the reliable reference points we use to determine which way is up. The mind, in short, is tricked.

In a 2006 Science Daily article, Brock Weiss, a physics professor at Penn State Altoona, investigates a gravity hill in Bucks County, Penn., and concludes that this local oddity isn’t that odd. “You are, indeed, going downhill even though your brain gives you the impression that you’re going uphill,” Weiss explains. Using GPS, the investigators demonstrated that the hill’s starting point had a greater elevation than its ending point, despite appearances to the contrary. And, if these mystery spots really were gravitational anomalies, wouldn’t your sense of balance and the objects around you be affected, instead of just your vehicle?

Just as I was pretty much convinced that I could put this into my “mystery solved” pile, Linda Collins of the Richford Historical Society brought me back into a sentiment of uncertainty. I phoned the town offices looking for answers, and instead had an awkward silence sent my way. I had almost thought they hung up on me, before the town clerk spoke up and said she had no idea what I was talking about. So she directed my call to Linda, who had a lot to say about Richford’s weird side.

“Oh yeah, I know about the hill. I think it’s called a ‘gravity hill’. I learned about it when I was researching the UFO sightings in town” said an amused Collins.

Back in the 1970s, she related, a few Richford residents reported seeing strange moving lights over town. Wanting to chronicle the frenzy for the Burlington Free Press, Collins made phone calls, which led her to a government facility in Boulder, Colo. She refers to it as “the strange things facility,” because “I don’t remember what they were called — it’s been so long since I’ve talked about this!”

According to Collins, the feds told her that a singular magnetic pull or gravitational force in the Richford area had the potential to “attract things.” They didn’t specify what things, and she surmised there was probably more that they weren’t telling her. “You know, government secrecy? They were probably doing some testing or something and didn’t want that getting out to the public,” Collins said. Later on, Collins learned of the “mystery spot” phenomenon.

“Does the historical society get many inquiries about it?” I asked. “No one up here really knows that much about it,” she said with a laugh. “It was such a small deal when it happened. Lots of folks in town now don’t really know a lot about our history anymore.”

“So what’s your opinion on it? Do you think it’s an illusion, or is there something actually weird with gravity in Richford?”

“Well….I mean, I don’t know what to tell you. Richford is a weird town. If all this business about the UFOs and gravitational pulls are true, then who knows.”

Border towns are weird in general, in both their local lore and for political complications and the infrastructure meant to delineate a sense of placement. Richford’s mythology resume is a bulky one of giant birds that have swooped down and snatched babies, UFOs, giant wolves that may live around the border, a possible “window area” near Jay Peak, and a former rendezvous for rumrunners and smugglers.

But Richford has it easy, compared to what may be New England’s strangest border community, which I hope to check out one day.

If the Richford, VT/Sutton, QC area really does have some sort of unique magnetic force, that would set Vermont’s mystery spot apart from the scores of others around the globe that can be debunked by aesthetic tomfoolery.

Because I was trying to write about this for Seven Days, I decided that was a great excuse to take another trip up to border country with another friend, and give it another go, this time in a Ford (if that makes any sort of difference)

Back up the East Richford Slide Road, we drove around looking for answers and an outlandishly cool experience, stopping and going almost the entire length of the slick road, with some situationally motivating Jazz coming quietly through the radio.

We think there was one spot where the car rolled in a direction that wasn’t backward, but after getting out of the car and scrutinizing the area, the very very gradual incline of the road may have actually been inconspicuously dipping downhill, but the eye is fooled from a larger uphill lip of an intersection beyond it which forms the horizon line. Was this the spot? If so, Dewing’s car was recorded going at least 15mph, while we were going 5.

I’m not sure if I left empty handed or not to be honest, but it was an enjoyable way to spend my morning.

Whatever the explanation for the mystique, the Richford Mystery Spot is still one of my favorite examples of Vermont obscura, because it’s accessible and fun. If only it were a little easier to locate the exact spot where the optical illusion — if that’s what it is — kicks in.

One of our many stops up the East Richford Slide Road, where we were definitely sliding all over the place.

The mowed down strip of forest cutting over those snowy mountains is an aesthetic reminder of where the U.S./Canada border is that’s called “The Slash”, created by homeland security when they deemed all of the 150 plus year old granite obelisk markers formerly doing the job as obsolete. So far, the clear cut runs from Maine to Minnesota, with the eventual finish line being Alaska. I read in a newspaper write up years ago that they defended their forestry project by arguing that a lot of Americans would be confused and wind up in Canada accidentally if they didn’t. I’m not sure if I buy that. I mean, I’ve never bumbled my way into Quebec before. But who are we to question the government?

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly! Especially now, as my camera is in need of repairs and I can’t afford the bill, which is distressing me greatly.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4

I woke up at 5 AM, was reminded that I wasn’t a morning person, and stumbled out my back door at 6. My friend was waiting for me in his parked car as the headlights cast a dull amber pallor onto quiet streets that were under the cold gray dawn. It was 41 degrees and I was all shiver bones in the new coming chill.

I stopped for a few gas station coffees and was rewarded with my early rise by wicked fog that obscured the landscape off route 7 in a glorious visceral veil that turned everything into mutated shadows. I caught some of it on my cell phone hanging around Dorset Peak, before it burned off.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BKwcFvFg9gG/?taken-by=the_tyranny_of_influence&hl=en

The weather lately has been prime for adventuring, and I’ve been aching to get out. This trip would give me that spark in my brains I was looking for. Feeding off my desire to visit as many obscure places as I can, I figured that two ghost towns in southern Vermont would be a great way to spend my day. These vanished places are probably some of the most obscure in the state. But everyone pays the price to feed, and I arrived back home exhausted and practically limping, so I suppose that can be gauged as one hell of an adventure. But I’m also someone who’d willingly drive 8 hours just to find an oddity, so a follow-up day of sluggish exhaustion was easily worth it for me.

Somerset

I’m willing to assume that plenty of Vermonters haven’t heard of Somerset. If you take a gander at a state atlas, it’s a narrow rectangle at the western edge of Windham County that nudges into eastern Bennington County – giving the latter county its block lettered “C” shape.

The entire burg is filled by the Green Mountain National Forest. It has a year-round population of 2 people and is only accessible by a forest service road that is all too easy to miss because of it’s small, squint-to-read street sign. But out of the two destinations I was planning on scouting, Somerset was the only one that was somewhat accessible by vehicle, so we started out with that one. I was still sipping my coffee which was getting unsatisfyingly cold, trying to shake off a road trip thematic Tom Waits song beating around in my head.

Somerset Road sort of plunges immediately down an embankment right off The Molly Stark Byway in woodsy Searsburg, and almost as quickly, turns to washboarded gravel after passing a few houses with scores of signs telling you that they’re not into people trespassing on their land. The increasingly destitute road now follows the Deerfield River and is thick with trees. We noticed that some older power lines had still been strung up along the road, and ran the length of the Searsburg portion. But it was evident these lines were archaic predecessors of modern day utility infrastructure. Some of the poles were leaning pretty horizontally as we got further down the road, and that’s when we noticed that they had glass insulators still on their lower rungs, now defunct as the power company had long clipped those wires and modernized things a bit a few feet higher up. Glass insulators were developed in the 1850s originally for telegraph wires, but were later utilized for initiative telephone wires and electric power lines, until the 1960s when they began to be phased out and simultaneously became a feature of interest.

I thought it was pretty cool to see them, and that there are still more or less untouched Vermont back roads that still exist. Older relics like these are becoming increasingly hard to find nowadays. And, apparently, there is a collectors market, clubs and even shows dedicated to them. Anything can have fanfare it seems.

As soon as we hit the Somerset town line, which was marked by an omnipresently strange country icon of a bullet-perforated speed limit sign and an abrupt transition of bad gravel road to worse gravel road. The power lines stopped, and for the next several miles, we were deep in the type of woods where you really couldn’t see the forest through the trees, and they were all in the throes of their glorious descent into their perennial death.

There are really no places in Vermont like Somerset. Though there are 2 census documented year-round denizens, the amount of people gets to about 24-ish during the summer months – they’re all people who have camps there. In a 2011 interview done by WCAX, one of two Somersetians, Don Gero, explained that people don’t stick around here. Both residents are bachelors, and he quipped that because Somerset has no electricity or phones, women don’t want to live there. “They can’t use their hair dryers or wash their clothes” he said. He’s also not happy about the summer camping population, who are “two dozen too many” for his tastes, and paeaned for the good ol’ days when I guess none of them were there. Often, the current culture of these odd places is more interesting than the past events that created them.

Charted by Benning Wentworth back when Vermont wasn’t Vermont and its land was quarreled over by New York and New Hampshire, the New Hampshire governor and businessman (in no particular order) just drew a whole bunch of lines on a map and granted towns without knowing anything of the area’s geography. The most important thing was that New York couldn’t get their hands on any of the land, so he didn’t concern himself with pesky things like that. Vermonters decided they preferred anarchy, and would later orgonize an independent republic in 1777 with our own currency and postal service, and then, the 14th state in 1791 when we tried on our current name.

Somerset is all mountains, far away from anything and hard to get to. Despite that it wasn’t great real estate to early settlers, 321 people tried to live here in the town’s 1880s apex. Logging was the only way to make a few bucks, so they deforested all of the area mountains. They attempted to have log drives down the Deerfield River, except for when it was low, which it was, a lot.

The demand for timber was ravenous, and that convinced a railroad line to lay tracks up to the mills, which were a huge boon to the town, but also helped speed up its death. A town depending on a finite resource comes and goes like fads always do, and most of the trees in the area were hacked down, the inevitable consequence was that both the logging industry and the town became a literal washout.

The town’s last hurrah was when the Deerfield River valley was eyed for a future facing wonder like hydropower and the cash it could bring. In 1911, the Somerset Dam began to take form. The dam was built by massive work crews of about 100 men in shifts, doing everything by hand and took about 3 years to complete. The reservoir did what reservoirs do best and collected the desired water, which submerged what was left of town and the railroad and the mills.

At some point, there was an airfield in Somerset, which has also vanished. Today it’s a free and minimal amenitied national forest campground under the same name. According to campers who post reviews online, it’s either wonderfully remote or a place where amateur outdoors folk or “Massholes” go to belt loud music and litter. Given my experience at campgrounds, I’d say it’s probably both.

I also found out, which isn’t detrimental to your life if you don’t know, that you can take class D forest roads from Somerset all the way north to the Kelly Stand Road – a west-east oriented forest road that’s also one of Southern Vermont’s most scenic. If you enjoy shunpiking, finding more of these back road byways to explore is usually not a bad thing.

A small and mowed cemetery surprisingly pops out of miles of wilderness as you travel up the forest road. Many of the weathered and matching headstones were kids. One sad entombment was uniquely chiseled with a sheep on top, and quickly caught my wondering eyes. Lancelot was 3 years old. Life up here was tough, especially for kids.

The further away from civilization we drove, the more apple trees started to distinguishly appear from the northern forests. I’m not sure how old some of these trees were, and if they were original to former Somerset residents, or planted after the national forest took over. These apple trees appeared somewhat haunted by the thick woods and lack of sunlight needed to grow. Others still carried apple crops which varied in how rotten they were. These apple strands that are heirloom seeds, and are not commercially available anymore in an increasingly lack of choice based GMO market, leaving these trees to one by one die off.

A brown and white national forest sign explained at the trees that were still able to produce apples were part of an “apples for wildlife program”,which is pretty self-explanatory.

I could have hung out in Somerset all day, it was just so beautiful and almost intimidatingly wild. All I’d need is a few Vermont microbrews to accompany me. This little brook paralleled the forest road, but I wouldn’t have found it if I didn’t stop to spark my interest in an old apple orchard.

Only 3 things remain of Somerset’s days as a town – one of them being its restored but locked one-room schoolhouse, also found a ways up the forest road. I heard it was a private camp, but not positive about those details. I’d love to see the inside. Or to live in a restored one-room schoolhouse.

The forests of Somerset. Are any of my blog followers into Geocaching like me? Somerset may be remote, but the area is loaded with caches!

The Somerset Reservoir is where the Somerset Road comes to an end, and in my humble opinion, one of the more stunning places in Vermont. The sinuous and currently blustery cold water body is about 5-6 miles long and undeveloped. The long form of Stratton’s rounded mountain top could be seen in the distance . The dam’s roadside appearance is really just a high grassy wall with a nearby unmanned rickety tin shack that has a TransCanada logo sign plate on it. But atop the dam is this awesome view of one of Vermont’s largest wilderness areas. I really wish I had brought a kayak or something. Seriously, places like this are therapy to me. I couldn’t contain my approval and swore a few times to prove it.

Glastenbury

Vermont author Joseph Citro introduced Connecticut’s faded hamlet of Duddleytown (which was really only a place name in the town of Cornwall named after the trio of brothers who bought land there) as “the granddaddy of all New England window areas” in his book Passing Strange, which to me made a pretty good lead-in to that chapter (it was actually the last sentence in his chapter on Glastenbury). I’d like to term swipe that to introduce Glastenbury on a more localized level, as the granddaddy of Vermont’s lost areas, for multifarious justifications.

Getting to the ill-fated town is nothing short of a challenge today, and was for the people who tried to make a life for themselves up there over a century ago. It’s isolation, stubbornly built up in an area of 12 peaks over 3,000 feet with no convenient access, makes it one of the most unique places in the Green Mountain State, then and now.

If you’ve been following my blog, you might know that I’ve been very interested in Glastenbury since I was a kid, and wrote about it extensively, my long winded self trying to pack as much detail as I could into a blog post. This entry expands on that.

To summarize things; the vanished town of Glastenbury was charted in 1761, and reflected the circumstances of its neighbor Somerset when it was naively plotted over some of the worst topography in the state. As a consequence, it wasn’t really until the 1850s when anyone paid interest to the town, when people figured out they had an entire mountain of wood to deforest for profit, and a logging/charcoal duality became Glastenbury’s only industry.

About 12 brick kilns for charcoal production were built in southern Glastenbury at an area known as “the forks”, because it was a distinguishable location where Bolles Brook split in two in a V-shaped parting of ways. A small and rough, lawless village designated as South Glastenbury grew up around these kilns, including a one-room schoolhouse, loggers boardinghouse and company store.

The steepest railroad ever built in the U.S. was developed to get up into South Glastenbury. The electric trolly line was the only element that made the town a pragmatic place; bringing down money making lumber and charcoal, and later, bringing up tourists. Many have no idea that aforementioned rail bed still exists, and if you follow it, will bring you deep into indistinguishable wilderness to the grave of the old town. Our adventure started well before we got out of the car when we navigated our way to the portal into the forest.

Funny enough, Glastenbury is still technically a town, at least in the haze of Vermont law. A gaze at a state atlas, or a Google map search, will show you a dotted lined square that represents a town boundary, only, there is nothing within the square. It’s considered an unincorporated town – or, one of 5 Vermont communities with a population so low, that instead of a town government handling its affairs, those things are managed by a county or the state. Or the national forest service I guess. There are a few people who still do live in Glastenbury – populated by just 6 people ( their properties are pretty much clustered near the borders of either Shaftsbury or Woodford), who also have achieved somewhat of a level of intrigue beyond the strange phenomena that describes the town.

I’m going to stay quiet on the access road we took, because it’s pretty evident that the people who have their addresses there don’t want the crowds. (Like the folks in Somerset, they live in the boonies for a reason, only, these folks express their discontent via threatening scrawl) When we drove up the gravel roadway, we immediately began to pass some shabby looking properties, all of them with handwritten and somewhat threatening signs warning nonlocals not to park their cars there, or else.

Fearing our car would be cannibalized for its wheels in an uncomfortable back woods “we warned you!” sort of situation, we decided to find what we designated as the safest parking space on the road, far away from any discernable houses and no parking signs. Hoping that we didn’t make a stupid mistake, we trekked up the road on foot, found the forest road, and began our hike into one of the most fabled places in state mythology.

This is a shot of the trail slash old rail bed, miles into our hike. Unexpectedly to me, this might be the most grueling of Vermont hikes I’ve endured. The amount of rocks ravished my feet to a point where I was literally limping down the trail, silently no longer caring if I was there and begging to rest my weary bones in the car.

Further up the trail, we started to find original rail spikes from when the railroad was built over a century ago!

This was a sign that got me revved up. We began to notice chunks of Slag along the trail. Slag is a stony waste matter separated from metals during the smelting or refining of ore, and since Glastenbury was built around charcoal furnaces, there is plenty of the stuff in the woods today. We were even to find some rare green and blue slag. I’m not very savvy about the jewelry culture, but I guess you can polish and buffer up slag chunks pretty attractively and make accented miscellany from them. I dig them in their natural form, and grabbed a few chunks of the green for my collection of oddities.

We hushed our sound as we heard another one that was all too familiar to me. We heard an approaching 4 wheeler. Because of my suspicious nature and not knowing what sort of people were this deep up in the woods, I decided to relocate myself as far to the side of the trail as I could, give a friendly nod and let them pass. As they got closer, I saw it was a younger couple, a man and a woman, and they slowed down as they saw us. I decided to take the mutual encounter and get past my social anxiety and spark up a conversation with them.

Actually, I wanted directions, because we were beginning to second guess ourselves as to where we were, and if we could find any of the ruins, and I really didn’t want to leave disappointed.

The front handbrakes were pulled and their 4 wheeler slowed down to a stop. The gentleman, who was wearing a camo baseball cap and sunglasses smiled at us and wished us a good afternoon, his wife sat behind him silently observing us with a friendly expression. I returned the greeting and asked him if he could direct us to South Glastenbury.

“Oh, the forks?” he asked. That casual nickname drop meant that they were aware of it, and I nodded my head, my excitement immediately betrayed my casual expression I was trying to keep. I also thought it was pretty rad that locals today still use the place’s old handle.

“Yes, the forks. Are we close? Would it even be traceable in all this?” I gestured to the thick woods around me to make a point. “Well, yeah you can find it. But this is sort of the wrong time of year to be looking for that sort of stuff. Also, it’s bear season up here you know. Uhh, how’d you guys know about Glastenbury, just curious?” he asked us with a backdrop set to his tone.

I wasn’t quite sure if my candor had triggered a nerve, or how to give him a cropped statement of how Glastenbury found itself sticking to the flypaper of New England mythology, but I had a feeling he already knew that. “So, you know about Middie Rivers?” his wife spoke up. “Yeah, I do” I stated. There was no need to be superfluous there. But for those of you who are unfamiliar with Glastenbury and it’s monsters;

Local lore includes a froth of big hairy monsters, a cursed Indian stone that swallows humans, UFOs, mysterious lights, sounds and odors detected by colonial settlers, and numerous hikers walking off the face of the earth here between 1945 to 1950 – earning it the nickname; “The Bennington Triangle” in 1992, which has adhered itself to the flypaper of popular culture.

Fortean researchers like John A. Keel conjured up the term “Window Area”, which I had referenced at the beginning of this section, as a place where some sort of interdimensional trapdoor can be found. Well, that’s one theory anyways. New England is loaded with so-called “Window Areas”. Cryptozoologist and researcher Loren Coleman identified Massachusetts’ “Bridgewater Triangle”, using the term “triangle” to designate any odd geographical area. Joseph Citro followed up by coining “The Bennington Triangle” – both are said to be “window areas” It’s also one of my favorite terms to use when talking about this caliber of local weirdness.

Who knows where the flickers of truth are in all this. And that’s what makes everything so damn fascinating, because there is truth in these tales tall and true.

It’s also the mountain’s paranormal and controversial tales that attract modern day professed ghost hunting clubs and social media sensationalists, whose meddling are an affront to both locals and reasonable judgment, which really seemed to have damned the wilderness area. Don’t get me wrong, these haunting stories are partially why I found myself hiking up the mountain, because of how impressionable they were and still are to me, but I find that there is also a line between being a civilized researcher, and becoming one of the monsters you’re chasing and exploiting it on a tawdry clickbait website with a headline that reads something like “{insert subject} will give you NIGHTMARES!”

Middie Rivers

The elderly Middie Rivers was the first of a handful of people who reputedly disappeared in the mountains in or near Glastenbury. Anyone who tells the story of southern Vermont’s Shangri-La recants that Rivers was an experienced woodsman who, while leading other hunters on the mountain, got a bit ahead on the trail, and was never seen again.

“None of that is true”, his wife said declaredly. “Rivers wasn’t a hunter or an experienced woodsman at all! He was actually from Massachusetts, and he had borrowed a rifle from his brother-in-law, who he was hunting with. He’d probably never even hunted before, and certainly never guided other hunters up here. The only thing that’s true about that story, is that he did disappear.”

“One theory is that he might have fallen down an old well. That seems pretty plausible to me”, I added. She nodded her head. “Yup, that’s what we think too. I mean, there are plenty of them up in the hills. But vanishing without a trace…people love to say that, because it backs up the mystic or, I don’t know, the ghostly impression about this place. They’d rather believe that than the facts, because it’s more interesting” she furrowed her brows and cut herself off in annoyed contemplation – like she knew what she wanted to say but couldn’t get it out. I was loving this conversation. “I know a bit about Middie Rivers” she continued after a moment. “I know a lot of stories and legends, passed down by relations to him. The Loziers – that’s the family who is related to him – we knew/know them, they passed down all sorts of stuff to us growing up. They have a camp up in Glastenbury still, like us. I even have a picture of Middie Rivers”.

“Ah, that explains the 4 wheeler then. I was a little surprised to see you folks! I assumed this was just a hiking trail or forest road”.

“Yup, we’re one of two camps in Glastenbury on this trail. My wife’s father built it years ago. We were grandfathered in. After the national forest took over, no one else was allowed to build up here or drive up this trail anymore. As it is, we need a special permit to have 4 wheelers so we can ride up here” – the husband cut in. “Did you see all of the gates?” I nodded in confirmation. We had to crawl underneath a few of them just to advance our hike. He continued; “We used to have friends up all the time, they used to come up in huge parties on ATVs up the trail. Now you can’t do that. It’s ridiculous, but hell, we’re not going to fucking lug all of our shit up to the camp on foot” – he then gestured to a cooler on the back rack of his 4 wheeler to emphasize his point. I got it. My friend and I had been walking for over an hour now, and I was already exhausted. “Our camps have been here for a long time – they started out as plywood cabins with dirt floors, and over the years as they were passed down, we’ve improved them a bit. No one else can build up here now.”

“I mean, it’s really probable that Middie could have fallen down a sink hole”, his wife interjected herself back into the already broadening conversation. “Sinkholes?” I asked, hoping I delivered a cue to get any sort of further information. “Ayuh, it happens more often than you think. Sinkholes swallow hunters all the time! There’s tons of them up here. People have hunted this mountain all their lives and still report getting turned around in the woods and intimidated here.”

“Because of the cross winds that meet on Glastenbury Mountain?” I prodded, a showing a little pride in my research. She nodded her head.

“I’d love to hear more about Middie Rivers, or any stories you guys have, if you’d be interested in chatting? I can give you my email or something?” I attempted. I couldn’t help it, I live for stuff like this. There is just something underneath my skin, a desire to make sense of everything. I’m definitely the type to overload myself with information.

At this point, his wife broke out in a lopsided grin and told me that she wasn’t interested in speaking any further about Glastenbury, without actually telling me she didn’t want to speak anymore about Glastenbury. “Well, we’ll be on our way now” said her husband, his thumb pushing the ignition and the engine promptly firing up. He gave us directions that were incredibly vague, but given the lack of wayfinding points, were the best he could do with people who’ve never been in those woods before. I thanked the both of them, tipped my hat in gesture, and both groups parted our opposite ways down the trail.

The Forks

It didn’t take long before we were unclear of the given directions and insecure about how much we remembered. It didn’t help that there were plenty of brook forks along the trail, tripping my thoughts up to think that any of them could be the forks.

As we continued our trek up the trail, we sighted something that sort of sketched us out. I’m laughing to myself as I type this sentence, but it was a cozy looking, nicely upkept log cabin which was probably one of the camps the baseball capped guy was talking. There was an open lawn area out front that was mindfully mowed and solar panels on the roof, with an outhouse in back. It’s hard to explain what it is about off grid living, or seeing a home way out in the boonies, that sends odd reactions that crawl up your spine. I suppose that so many of us are just accustomed to being hooked up to utility poles (in some more repressive states, it’s actually against the law to be off the grid), that this sort of makes us subconsciously weary, like there is something “weird” about the arrangement, and easy to stereotype the people that chose to live like that and how they’re of their own sort. But then I remember that I’d live like that too if I could.

But still, I picked up my pace a bit, wanting to get out of sight of the cabin and back into the woods. Then, we ran into another fellow on a 4 wheeler. This time, our approaching character was an older gentleman. We side-stepped off the trail again, nodded our heads, and went through the same rounds of introductions as last time.

“The forks, huh? Well, I mean….you can’t make out much of the old hotel foundation anymore, but it’s right off this trail. Nothing much left of the kilns. Might be some iron bands, maybe bricks.” Then he pointed to an offshoot 4 wheeler trail that ran through an area thick with prickers and berry bushes. “There’s more kilns up that knoll there” he said, his wisdom rolled confidently off his tongue wrapped up in his heavy Vermont accent. “Oh, uh, that trail looks like it goes behind the camp we just passed,” I said uncomfortably. Though my hobby of exploration often involves trespassing, I wasn’t about to skulk around someone’s land up in those hills, especially inhabited land. People in the boondocks have guns. “They aren’t home are they?!” He said, a little wonderment in his inotation.

“No, we didn’t see anyone when we walked by”, I returned, grinning at his unexpected humorous reaction.

“Oh, good!” he said, his enthusiasm almost made me crack up. I wondered if they got along or not. “But yeah – there’s more of em’ down that trail. Well, I’ve never seen them, but I know they’re there!” This time, I didn’t contain my mirth. I liked this guy. I asked him to clarify our misdirections a bit, and he gave us some of the most Vermont directions I’ve ever gotten – far superior to the ones I got when searching for some of our state’s mysterious stone chambers.

“Well, when you get to the forks, take a right instead of the left crossing over the brook, then go up the mountain a ways but still make sure to parallel the river – look down and you’ll eventually see the kilns. Or what’s left of ’em anyways. ” Just then, a Glastenbury traffic jam formed behind the old timer on his 4 wheeler, as three teenage rednecks on dirtbikes pulled up and sort of just looked at my friend and I stoically, the last one in line revved his engine impatiently while refusing to make eye contact and tried to flaunt his, I don’t know, machismo? Or maybe he was just impatient. I shook his hand and wished him a good afternoon, and we were on our way.

More walking down the trail later, and we approached a very standout fork in Bolles Brook and the rail bed portion of the trail we were on ended and transitioned into a slender path beyond a wooden bridge that crossed the brook. We had found the forks.